8 Travel Tips from an 1881 "How To Travel" Guide

As with every historical travel book I find, the particulars and prose place the reader in another time, yet people will be people.

This pocket-size piece, How to Travel: Hints, Advice, and Suggestions to Travelers by Land and Sea All Over The Globe by Thomas Knox was published in 1881. The version I found at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia was distributed by The Erie Railway, which included advertisements in the back.

As with every historical travel book I find, the particulars and prose place the reader in another time, yet people will be people.

This pocket-size piece, How to Travel: Hints, Advice, and Suggestions to Travelers by Land and Sea All Over The Globe by Thomas Knox was published in 1881. The version I found at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia was distributed by The Erie Railway, which included advertisements in the back.

It’s packed with hints, advice, and—you guessed it—suggestions. As you’ll see, some things just don’t change.

1. IF YOU UNDER-DECLARE AT CUSTOMS, BE CHILL ABOUT IT

“Declare anything that may be liable to duty and call attention to it, and conduct yourself generally as though it was one of the delights of your life to pass a custom-house examination.”

If you are inclined to defraud the revenue, do it gracefully and conceal your contraband articles so that it will not be easy to find them yourself after you are out of reach of the officials.

“Honesty is, however, the best policy in this business, and the smuggler is just as much a violator of the law as a burglar.”

2. ALWAYS CARRY CHANGE

“Even where they [service industry workers] admit that they are possessed of small coin, they generally manage so as to mulct you in something by having their change give out before the proper return is reached. The New York hackman to whom you hand a five-dollar bill for him to deduct his fare of two dollars will usually discover that he has only two dollars, or perhaps two and a half, in his possession; and the London cabman will play the same trick when you ask him to take half a crown from a five-shilling piece. All over the world you will find it the same. There may be an occasional exception, but it only proves the rule. And when you enter the great field of gratuities, you will find that the absence of small change will cost you heavily.”

3. DON’T PLAY EUCHRE WITH STRANGERS!

“Beware of playing cards with strangers who wish to start a friendly game of euchre which is subsequently changed to draw-poker or some other seductive and costly amusement. This advice is superfluous in case you are in the gambling line yourself, and confident that you can "get away" with any adversary you may be pitted against.”

A Travel-size Travel Guide!

4. LOCK YOUR DOORS FROM SCOUNDRELS!

“A crowded steamboat at night is the paradise of the pickpocket, who frequently manages to reap a rich harvest from the unprotected slumberers. Even the private rooms are not safe from thieves, as their occupants are frequently robbed. On one occasion, some thirty or more rooms on a sound steamer were entered in a single night. The scoundrels had obtained access to the rooms in the day-time, and arranged the locks on the doors so that they could not be properly fastened.”

5. RESERVE YOUR CHAIRS

“If you are of a sedentary habit, buy a steamer chair, and when you buy it make up your mind that you will occupy it when you want to. A great number of people who say they "don't want the bother of a chair," or "didn't think to get one," are in the habit of helping themselves to the chairs of others without the least compunction of conscience and without caring a straw as to the desires of the owners for their property. Women are worse offenders than men in this matter, and the young and pretty are worse than the older and plainer.”

“If you have a stony heart you will turn an intruder out of your chair without ceremony, whatever the age or sex, but if you cannot muster the courage to do so your best plan is to send the deck steward to bring the chair, and while he is getting it you can remain quietly out of sight. “

6. NO ONE LIKES A CRUISE SHIP GOSSIP!

“A ship is a world, and the ocean is the measureless azure in which it floats. Sea and sky are your boundaries, and the horizon-line is ever the same. The weaknesses of human nature, as well as its noble qualities, are developed here, and sometimes they are limned in sharper outlines than on land.”

“Persons whom you have known for years will develop on shipboard qualities that you never suspected them of possessing.”

“You had always thought your neighbor on the right was a selfish mortal, but you now find that he is self-sacrificing to the extreme; on the other hand, the man whom you believed a model of politeness turns out to be quite the reverse. Never in your life have you heard as much gossip in a month as you now hear in a single week; the occupation, character, peculiarities, hopes, desires, and frailties of everybody are canvassed by a goodly proportion of busy tongues, and the ship will very likely impress you as a school for scandal which Sheridan might envy.

Don't take a share in the gossip, and don't concern yourself about the private affairs of anyone else. Be polite to everybody, but don't be in a hurry to make acquaintances; by so doing you will stand higher in their estimation, and will have time to find out those whom you would like the best.”

7. EVEN THE ARGONAUTS GOT SEASICK

“Sea-sickness is a mystery, and the more we study it the more are we at sea as to its exact operation.” (Marc here: Thomas Knox totally smiled after writing that sentence.)

“[Dr. Baker] also recommends a person about making a sea-voyage to take a supply of "mustard leaves," which can be had at the druggist's. They are useful in allaying the nausea and vomiting by getting up a counter irritation, and should be applied over the pit of the stomach."

LAST BUT NOT LEAST…

8. IT’S OK TO CRY WHEN YOU LEAVE YOUR SHIP

“As we leave the ship that has brought us safely over the ocean, it will be no discredit to our manhood if we say good-bye to her, and wish her many prosperous voyages. A feeling akin to affection is not infrequently developed by the traveler for the ship that has carried him, and ever after he will take a personal interest in her fortunes.”

Along Alaska's Great River by Frederick Schwatka - First Edition

Today, I met Frederick Schwatka, an Army lieutenant and explorer who, in 1883, floated with six other men down all 1,300 miles of British Columbia’s and Alaska’s wild, unforgiving Yukon River on a purpose-built river boat.

Did I say boat? I meant raft— a simple, unwieldy, 16’x42’, almost silly-looking log raft rowed at max speed 1-mile-per-hour (hold onto your fur-lined hats!)—for one of the most important river journeys in western exploration.

Today, I met Frederick Schwatka, an Army lieutenant and explorer who, in 1883, floated with six other men down all 1,300 miles of British Columbia’s and Alaska’s wild, unforgiving Yukon River on a purpose-built river boat.

Did I say boat? I meant raft— a simple, unwieldy, 16’x42’, almost silly-looking log raft with maximum row speed of 1-mile per-hour (hold onto your fur-lined hats!)—for one of the most important river journeys in western exploration.

Published in 1885, Along Alaska’s Great River is Schwatka’s travelogue from Portland, Oregon, ascending the inland (or inside) passage to Alaska as far as the “Chilkat country,” where he and his men employed over three-dozen Chilkats to help them traverse the glacier-clad Chilkoot Pass of the Alaskan range to the headwaters of the Yukon. From there, they passed through 150 miles of lakes, rapids, etc., before floating down the main Yukon flow for over 1,300 miles. At the time, it was the longest raft journey ever recorded ‘in the interest of geographical science.’

And they did all on this…

Are you kidding me?

The thought of this 1,300-mile journey being undertaken aboard a raft without cover is mind-boggling. Even Schwatka, who’d previously endured a grueling 2,700-mile sled exploration to search for the lost Franklin Expedition, scratched his head in retrospect.

How many libraries have their books with the original “Received Dec 12, 1885” stamp?

“Looking back, it seems almost miraculous that a raft could make a voyage over thirteen hundred miles, the most difficult part of which was unknown…The raft is undoubtedly the oldest form of navigation extant, and undoubtedly the worst.”

In books with prose often as dry as their centuries-old bindings, I was pleased to see Schwatka’s story peppered with playful wit, bordering on Twain—like here, on the way north from Portland, when his positioning ship stopped in Victoria, British Columbia on the Queen’s birthday.

“Our vessel tooted itself hoarse outside the harbor to get a pilot over the bar (shoal), but none was to be had till late in the day, when a pilot came out to us showing plainly by his condition that he knew every bar in and about Victoria.”

From Victoria, the ship continued north, through Queen Charlotte Sound, which I’ve sailed through several times, the most recent with glassy waters made rough only by surfacing whales. Schwatka and his men weren’t so lucky.

“…we again felt the “throbbing of old Neptune’s pulse,” and those with sensitive stomachs perceived a sort of flickering of their own.”

Learn as you go. That’s a key takeaway from my research of historical travelogues. Set a goal. Make it huge. Get people excited about it. Raise money to do it. Plan as well as possible. Start it. Then fight like hell to survive because your idea of your capabilities relative to nature’s is nowhere near correct. The seven-man raft crew seemed especially to have their hands full in this regard.

“…too often in the most trying places our experiments in testing the questions were failures, and with a sharp snap the oar would part…and the craft like a wild animal unshackled would go plowing through the fallen timber that lined the banks…We slowly became practical oar makers, however, and toward the latter part of the journey had some crude but effective implements that defied annihilation.”

Once again, I am astounded at the resolve and skill of these men to accomplish such a herculean task. That of the topographer is especially impressive.

“The errors in dead reckoning of Mr. Homan, my topographer, in running from Pyramid Harbor in Chilkat Inlet to Fort Yukon, both carefully determined by astronomical observations and over a thousand miles apart, was less than one percent…”

Like most explorers of the day who penned a travelogue, Schwatka is all plot, tight lipped with private feelings. But—be it a square-rigger or a bunch of logs lashed together—a captain’s bond with his vessel is special and unique in exploration—enough to make the crustiest sailor shed a tear. Here, Schwatka’s words at the end of the story say it all.

“Here too, the old raft was laid away in peace, perhaps to become kindling-wood for the trader’s stove. Rough and rude as it was, i had a friendliness for the uncouth vessel, which had done such faithful service, and borne us safely through so many trials, surprising us with its good qualities. It had explored a larger portion of the great river than any more pretentious craft, and seemed to deserve a better fate.”

An incredible accomplishment, and a nice read overall. Unfortunately, Schwatka’s personal story ended a few years later, with his death at 43—a morphine overdose deemed suicide. He seemed to deserve a better fate too.

Along Alaska’s Great River by Frederick Schwatka was read thanks to a membership at The Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Holding History: 1744 Printing of The Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels

“Feels pretty complete,” I said as I held the ten-pound, nine-hundred-page beast of a book. Published in 1744 as the definitive collection of world travels, The Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels Consisting of Above Six Hundred of the Most Authentic Writers…(the title goes on forever)…by John Harris, is a fascinating read. While the theme of The Principal Voyages and Discoveries came courtesy of the Wu Tang Clan’s C.R.E.A.M. (cash rules everything around me), this tome leans more towards “knowledge is power.”

“Feels pretty complete,” I said as I held the ten-pound, nine-hundred-page beast of a book. Published in 1744 as the definitive collection of world travels, The Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels Consisting of Above Six Hundred of the Most Authentic Writers…(the title goes on forever)…by John Harris, is a fascinating read. While the theme of The Principal Voyages and Discoveries is pure capitalistic domination, this tome leans more towards “knowledge is power.”

On the push to the north pole and northwest passage:

“…experience has taught us that the knowledge of the dark and dreary regions is very far from being useless and unprofitable, and still farther from being dry or unentertaining.”

I’m a sucker for foldout maps.

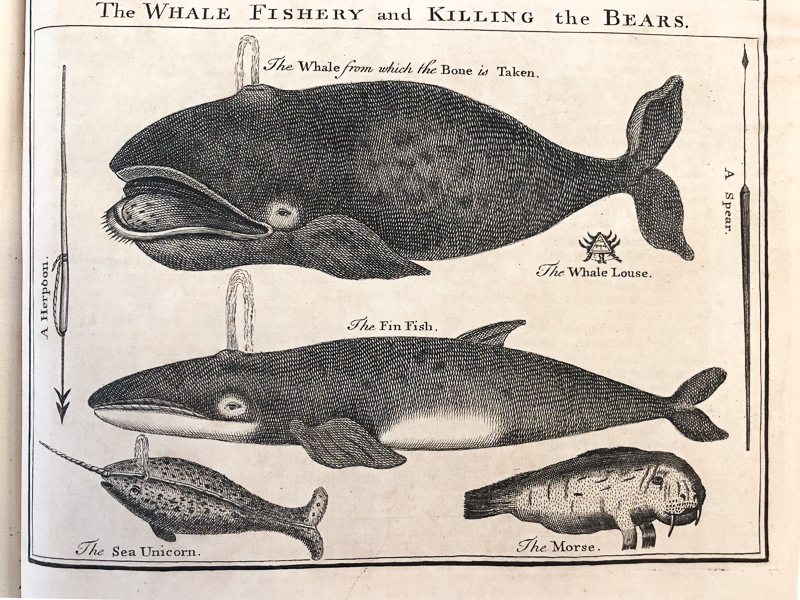

Notice the “sea unicorn” is a narwhal whale and “the Morse” is a walrus (strangely crude compared to the whale renderings).

While the drawings and descriptions of wildlife and distant lands are detailed and entertaining, I was most taken by Oxford academic Henry Maundrell’s account of Jerusalem in the late 17th century.

“When we came to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, we found it crowded with a numerous Mob, who began their disorders by running round the Holy Sepulchre with all their Might, crying out Huia, i.e. This is he or this is it; by which they express the Truth of the Christian Religion. After, they began to act many antic tricks, like mad-men; sometimes they dragged one another round the Sepulchre, sometimes they set one man upon another’s shoulders, and so marched round; and sometimes they tumbled round the Sepulchre like tumblers on a stage, and acting the rudest things on this occasion.”

“You, sir, are acting the rudest!” I love it.

I am far from a scholar, so I read these old travel accounts with naïveté. But I do know tourism, and when I found Maundrell’s description of ancient entry fees at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, I simply nodded along.

“We found the church doors guarded by Sanizaries (soldiers) who suffer none to go in until they have paid their Caphar, which for Franks is commonly fourteen dollars per head, unless they be ecclesiastics, and then it is but half as much. This being once paid, you may go in and out gratis as oft as you please during the whole feast at the ordinary times when the door is open.”

This could be a fancy guy’s TripAdvisor review, yet his journey took place 322 years ago!

Also as of 322 years ago: The Great Wall when it was only “famous.”

And Florida when it was only a little nub.

There is so much to love about this book’s content and the book itself—a masterwork of publishing. Just remember, lift with the legs.

Made possible by my membership to The Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Holding History: The 1589 Printing of The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation

Before we even get started on this book’s content, I have to finish writing the title: The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation Made By Sea or Land to the Farthest, Distant Quarters of the Earth at Any Time Within The Compass of these 1600 Years.

Wait, wait! I haven’t finished writing the book’s title yet: The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation Made By Sea or Land to the Farthest, Distant Quarters of the Earth at Any Time Within The Compass of these 1600 Years.

You get all that?

It is by Richard Hakluyt, an English writer, preacher and “sometime student of Christ-Church in Oxford.” (It actually states that in another version of the book.)

Once again, I was able to hold this piece of travel and publishing history thanks to my membership at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, an independent member-supported library in operation since 1814. It is my favorite writing spot in the city, which I want everyone and yet no one to know about.

Like that font? It’s called Migrain. My eyes hurt after only a few lines. But what this book lacked in legibility, it gained in the sheer fact that it was written during the era of Queen Victoria I (the Uno) and I was able to hold it.

The chapters are quite literally all over the place. Bits of a voyage to Guinea, trips to Norway detailed so slowly and somehow still with so few details that I didn’t care if they made it or not, and a description of a woman, Helena, who seems to have been quite a catch back in the day. If I can sum up the 800-page tome in one line, and British exploration at that time too, it would be: “We heard they had stuff. We wanted it. Here’s how we got it.”

To pull from the book:

“Experience proveth that naturally all Princes be delirious to extend and enlarge their dominions and kingdoms.”

Another line stated that rulers who do not try to conquer others will be seen as weak by their people, and not respected. So, they sought distant lands and riches. Terrible things happened to the native inhabitants. The spoils went to the English ruling class.

Notice the change in font and style half way through “Richard Eden” in the title? That’s a 16th Century moveable type “whoops!”

As for the prose, I can only shrug. “…the regions are extremely hot and the people very black,” one story says of Africa. AFRICA!

Can’t you just feel the wind in your hair as you walk the Great Rift Valley with the Maasai, learning the mysteries of the land gleaned from millennia of oral history? Nailed it.

Several paragraphs ended with:

“And to have said this much of these voyages, it may suffice.”

Or “And to have said this much on elephants and ivory, it may suffice.”

Which is the British origin of Forest Gump’s, “And that’s all I have to say about that.”

BUT WAIT!

What REALLY made this book a treasure to hold, beyond its age, is that it was gifted to the Athenaeum by Mathew Carey (1760-1839), an Irish-born American publisher and economist who lived and worked in Philadelphia. And like any good Philadelphia story, his involves Ben Franklin, railing against the establishment, and cross dressing.

Carey started his career in Ireland as a bookseller and printer but got into trouble with the British House of Commons after publishing works that criticized the Irish Penal Code, Parliament, and dueling—not a fan. Carey fled to France where he wound up meeting and befriending Benjamin Franklin. (Because who DIDN’T know Ben Franklin back then?)

After working for Franklin for a year at his printing press in Paris, he emigrated to the newly formed United States in 1784. Upon his arrival, he was given $400 by Franklin’s buddy, Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (American Revolution, French Revolution, Napoleon. That Lafayette.) to set up his own publishing business and book shop. He became one of the biggest publishers in the country.

Oh, and since he had ticked off the British so badly, when he went from France, back to Ireland and then to America, he had to dress as a woman and sneak on the ship to avoid imprisonment. Because freedom.

To hold the book of the man who once shook Ben Franklin’s hand, Lafayette’s hand, and became a publishing tycoon in the early days of this country was a pretty mind blowing experience.

And to have said this much of Mathew Carey and his copy of The Principal Navigations, it may suffice.

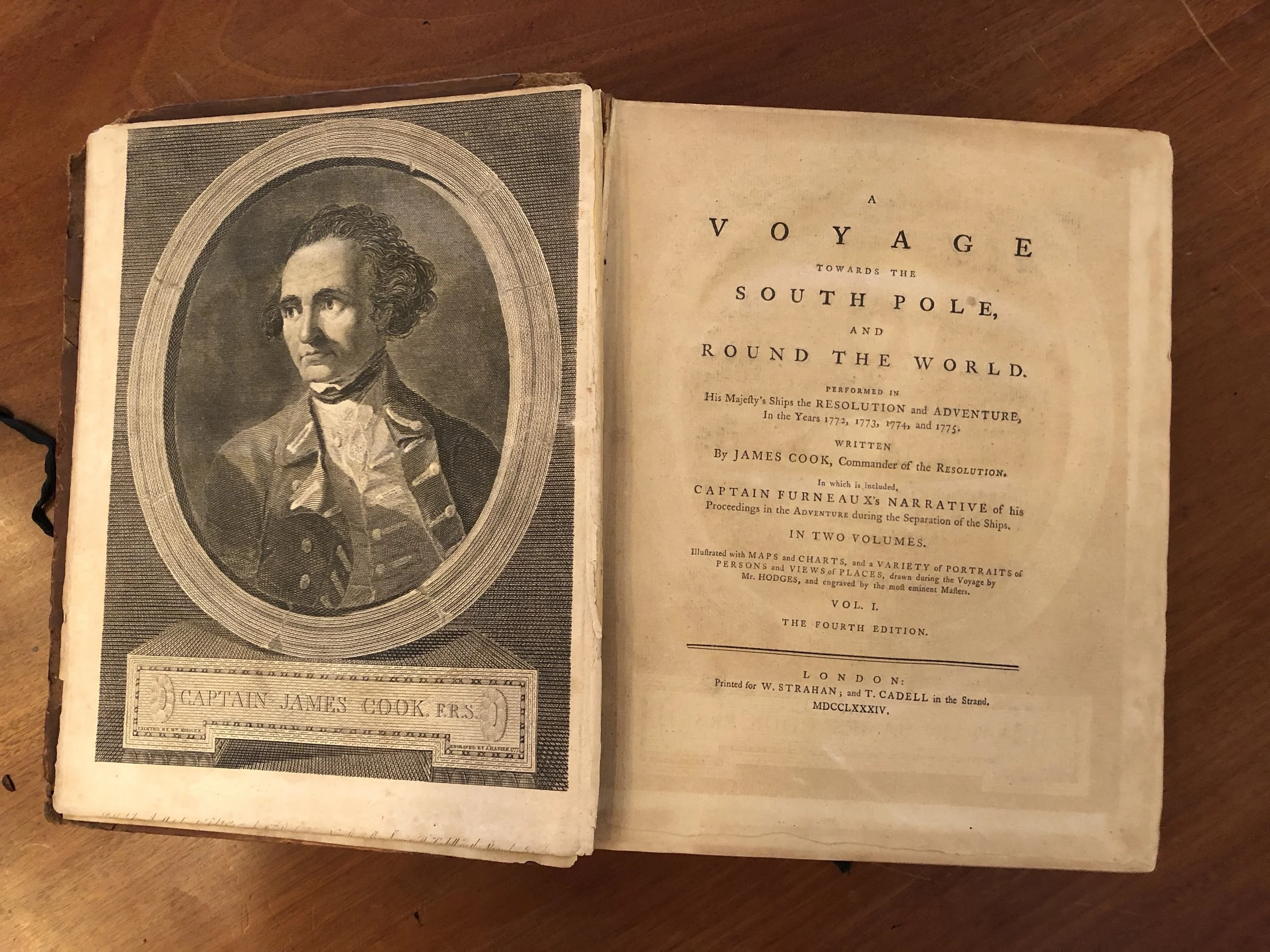

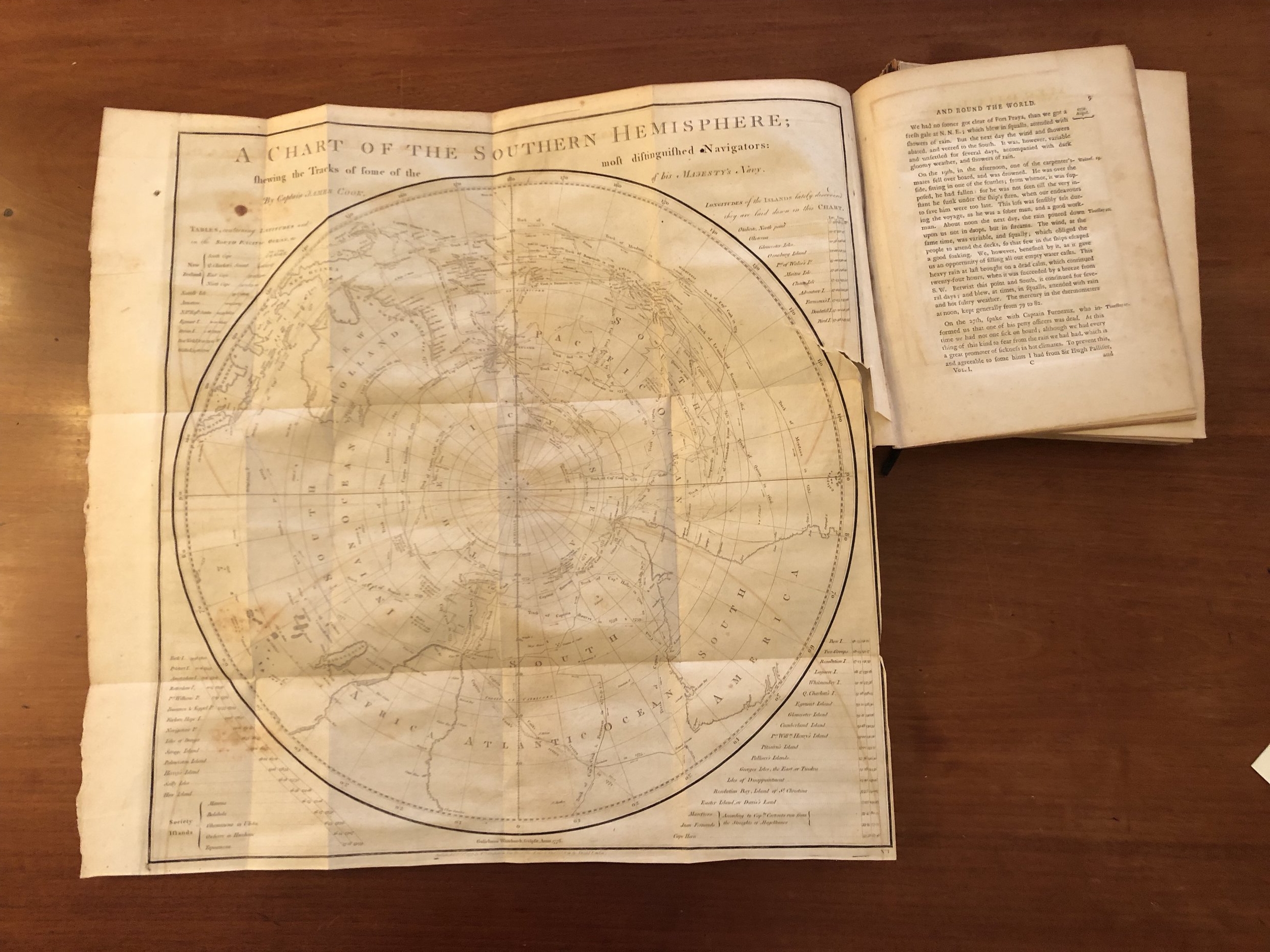

Holding History: The 1784 Printing of Captain James Cook's Voyage to the South Pole and Round the World

"There's just something about a book in your hand" went to another level today as I read through a 1784 printing of A Voyage Towards The South Pole and Round the World by Captain James Cook.

"There's just something about a book in your hand" went to another level today as I read through a 1784 printing of A Voyage Towards The South Pole and Round the World by Captain James Cook.

I had to be extremely delicate with the pages, since the leather binding was extremely brittle. Thanks to the Guttenberg project, the entire book is available to read online for free. But going through the physical printing of Captain James Cook’s Voyage to the South Pole and Round the World helped me feel the 18th century in Cook's words. Frankly, it read like many other travelogues I've come across. Good weather, bad weather, intentions, outcomes, lively characters along the way. Like its leather cover, the prose was a little dry. BUT this was printed two hundred and thirty four years ago!!!

Readers' minds must have been blown by the descriptions of the people he met with, chiefs, the tropical shores, seas filled with ice, the exotic foods. Cava? What? (How many people TODAY don't know what cava is?)

If you are into modern travel stories you might want to take a look at the writings of the old explorers as well. Shackleton, Cook, even Mark Twain and The Innocents Abroad (one of my all time favorites). It’s amazing how evergreen some of the descriptions are, of the places but also of the experience of travel itself.

Who doesn’t love a foldout map?!? (BTW, it was already ripped when i opened it.)

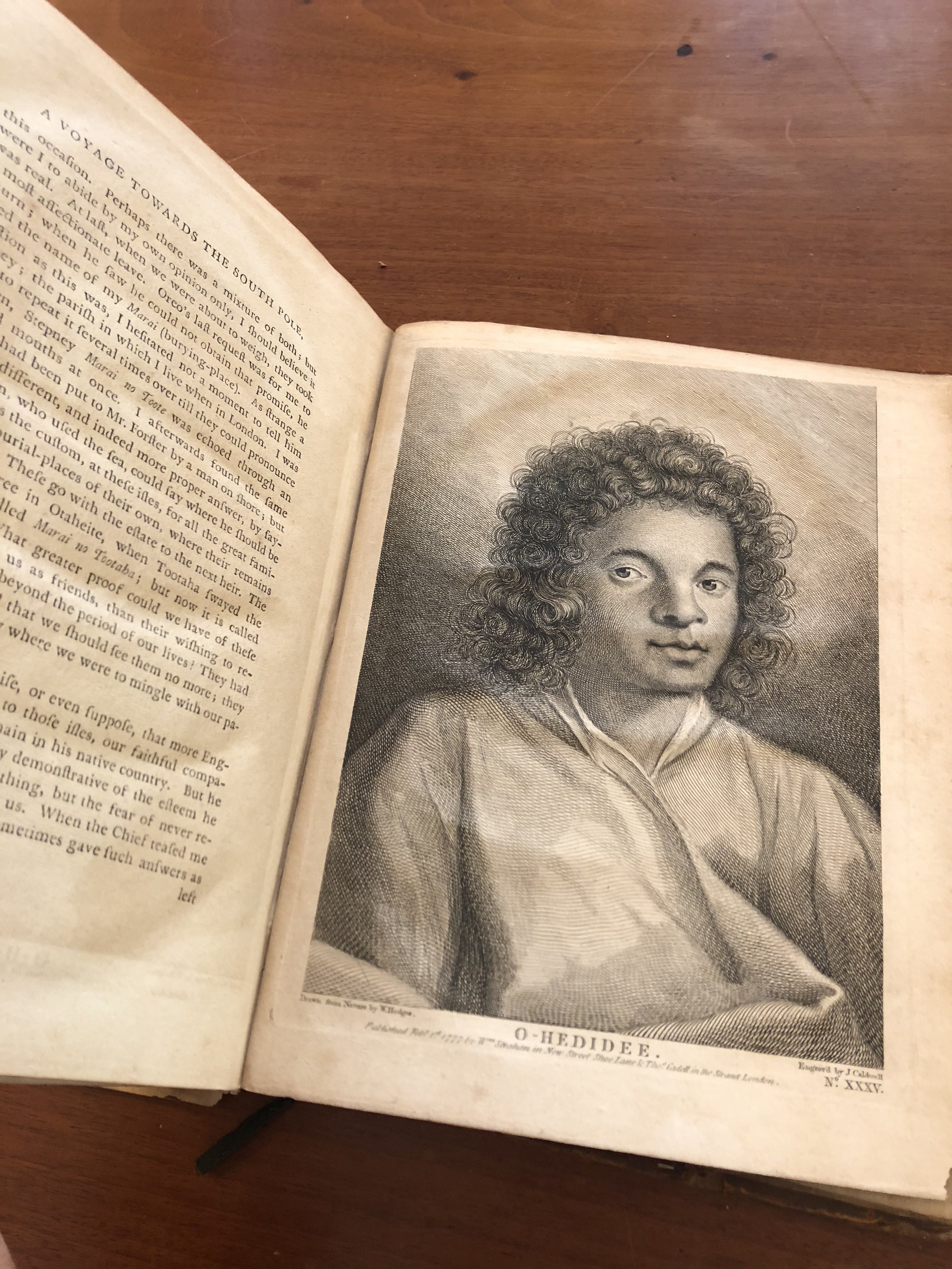

The drawings are by William Hodges, who made them during the voyage and accompanied Captain Cook on several adventures.

Thanks to the Athenaeum of Philadelphia for once again letting me hold a ridiculously cool piece of travel history!

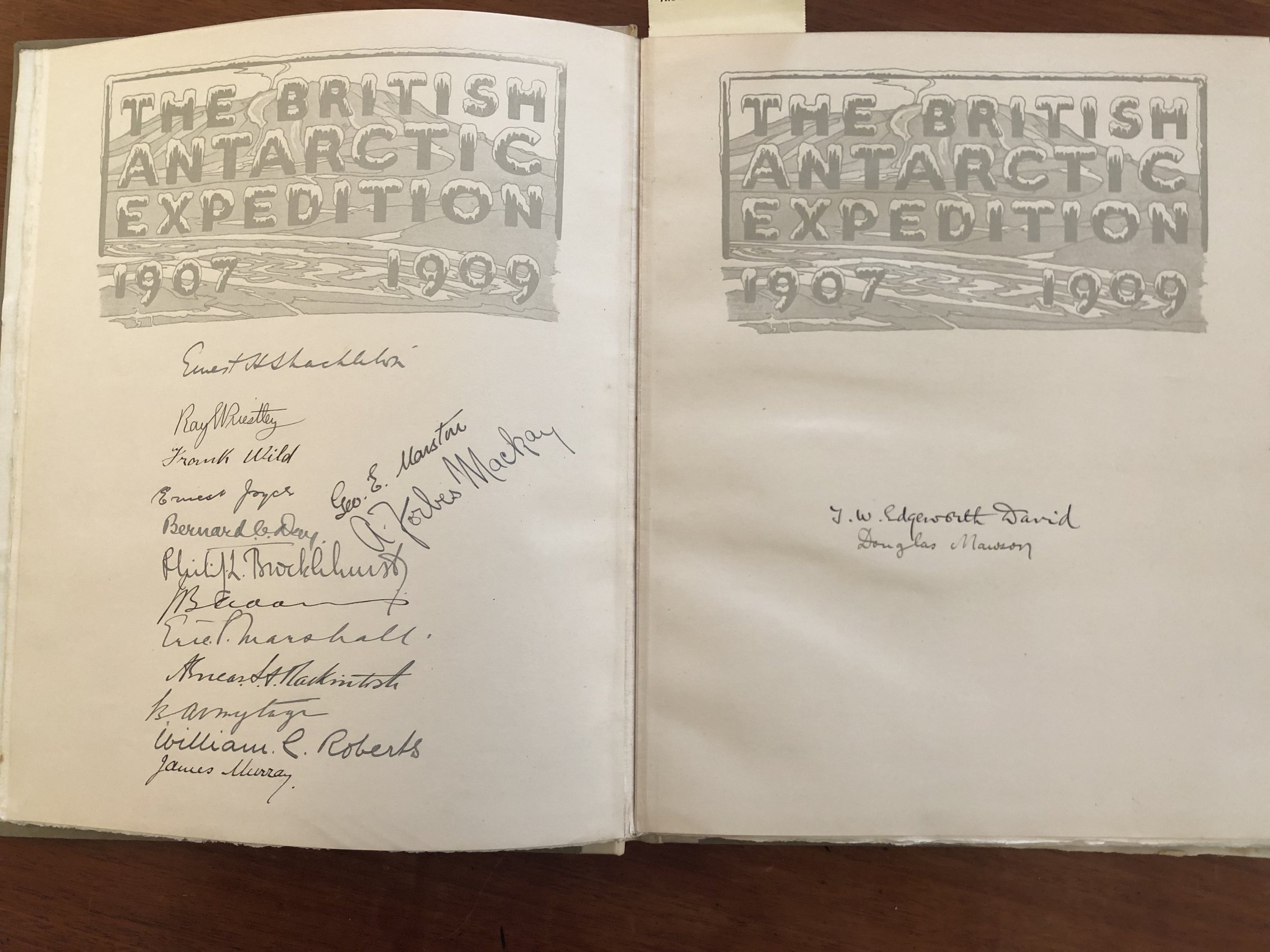

Holding History - Ernest Shackleton and the Special Edition Heart of the Antarctic

“Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by the love of adventure, some have a keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the “lure of little voices,” the mysterious fascination of the unknown.”

“Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by the love of adventure, some have a keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the “lure of little voices,” the mysterious fascination of the unknown.”

So begins Ernest Shackleton’s Heart of the Antarctic, which documents his 1907-1909 journey aboard The Nimrod. I have the pleasure of reading a white, leather bound, limited edition 1909 William Heinemann printing at The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, an independent, member-supported library and museum.

Reading this book brings me out of body. It is one of only 300 copies printed in London one hundred and nine years ago. The paper edges are rough as tree bark. It smells old. The photos and drawing inserts are hand glued in place. But what makes this copy particularly rare is that it's signed by Sir Ernest Shackleton with an inscription to his friend in Philadelphia, whom he thanks for his hospitality and shares "good wishes on the coming Christmas."

Page after worn page, I'm well aware that I am touching something that The Boss (not Springsteen) held a year before leaving for his famed Endurance expedition.

I marvel at descriptions of what the men endured, the list of supplies, the cost of the expedition--£44,380 (or £5,059,320.00/ $6,554,667.80 USD today).

When I look at the map I note how close the shore party was to the pole when Shackleton called it quits. Two degrees latitude. Two measly degrees. That’s New York to DC, Chicago to Indianapolis, Orlando to West Palm. It's also the difference between life and death.

The Athenaeum has both volumes of Heart of the Antarctic here, plus "The Antarctic Book," which contains poems (Erbus from Shackleton) and other interesting bits from the voyage. This version happens to be signed by the entire shore party, which included Frank Wild, who also joined Shackleton on the famed Endurance voyage.

After sitting with the books for hours, I leave them and step out into the muggy Philadelphia summer. I'm feeling adventurous. By Queen Village, I start hearing the lure of little voices. They tell me to go somewhere cool. Somewhere icy. Maybe Antarctica. Maybe the Arctic.

I end up at John's Water Ice on 7th Street. A medium cherry/lemon hits the spot.

Photos hand-glued in place.

They couldn't do better than Lipton's Tea???