Holding History: The 1589 Printing of The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation

Before we even get started on this book’s content, I have to finish writing the title: The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation Made By Sea or Land to the Farthest, Distant Quarters of the Earth at Any Time Within The Compass of these 1600 Years.

Wait, wait! I haven’t finished writing the book’s title yet: The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation Made By Sea or Land to the Farthest, Distant Quarters of the Earth at Any Time Within The Compass of these 1600 Years.

You get all that?

It is by Richard Hakluyt, an English writer, preacher and “sometime student of Christ-Church in Oxford.” (It actually states that in another version of the book.)

Once again, I was able to hold this piece of travel and publishing history thanks to my membership at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, an independent member-supported library in operation since 1814. It is my favorite writing spot in the city, which I want everyone and yet no one to know about.

Like that font? It’s called Migrain. My eyes hurt after only a few lines. But what this book lacked in legibility, it gained in the sheer fact that it was written during the era of Queen Victoria I (the Uno) and I was able to hold it.

The chapters are quite literally all over the place. Bits of a voyage to Guinea, trips to Norway detailed so slowly and somehow still with so few details that I didn’t care if they made it or not, and a description of a woman, Helena, who seems to have been quite a catch back in the day. If I can sum up the 800-page tome in one line, and British exploration at that time too, it would be: “We heard they had stuff. We wanted it. Here’s how we got it.”

To pull from the book:

“Experience proveth that naturally all Princes be delirious to extend and enlarge their dominions and kingdoms.”

Another line stated that rulers who do not try to conquer others will be seen as weak by their people, and not respected. So, they sought distant lands and riches. Terrible things happened to the native inhabitants. The spoils went to the English ruling class.

Notice the change in font and style half way through “Richard Eden” in the title? That’s a 16th Century moveable type “whoops!”

As for the prose, I can only shrug. “…the regions are extremely hot and the people very black,” one story says of Africa. AFRICA!

Can’t you just feel the wind in your hair as you walk the Great Rift Valley with the Maasai, learning the mysteries of the land gleaned from millennia of oral history? Nailed it.

Several paragraphs ended with:

“And to have said this much of these voyages, it may suffice.”

Or “And to have said this much on elephants and ivory, it may suffice.”

Which is the British origin of Forest Gump’s, “And that’s all I have to say about that.”

BUT WAIT!

What REALLY made this book a treasure to hold, beyond its age, is that it was gifted to the Athenaeum by Mathew Carey (1760-1839), an Irish-born American publisher and economist who lived and worked in Philadelphia. And like any good Philadelphia story, his involves Ben Franklin, railing against the establishment, and cross dressing.

Carey started his career in Ireland as a bookseller and printer but got into trouble with the British House of Commons after publishing works that criticized the Irish Penal Code, Parliament, and dueling—not a fan. Carey fled to France where he wound up meeting and befriending Benjamin Franklin. (Because who DIDN’T know Ben Franklin back then?)

After working for Franklin for a year at his printing press in Paris, he emigrated to the newly formed United States in 1784. Upon his arrival, he was given $400 by Franklin’s buddy, Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (American Revolution, French Revolution, Napoleon. That Lafayette.) to set up his own publishing business and book shop. He became one of the biggest publishers in the country.

Oh, and since he had ticked off the British so badly, when he went from France, back to Ireland and then to America, he had to dress as a woman and sneak on the ship to avoid imprisonment. Because freedom.

To hold the book of the man who once shook Ben Franklin’s hand, Lafayette’s hand, and became a publishing tycoon in the early days of this country was a pretty mind blowing experience.

And to have said this much of Mathew Carey and his copy of The Principal Navigations, it may suffice.

Holding History - Ernest Shackleton and the Special Edition Heart of the Antarctic

“Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by the love of adventure, some have a keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the “lure of little voices,” the mysterious fascination of the unknown.”

“Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by the love of adventure, some have a keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the “lure of little voices,” the mysterious fascination of the unknown.”

So begins Ernest Shackleton’s Heart of the Antarctic, which documents his 1907-1909 journey aboard The Nimrod. I have the pleasure of reading a white, leather bound, limited edition 1909 William Heinemann printing at The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, an independent, member-supported library and museum.

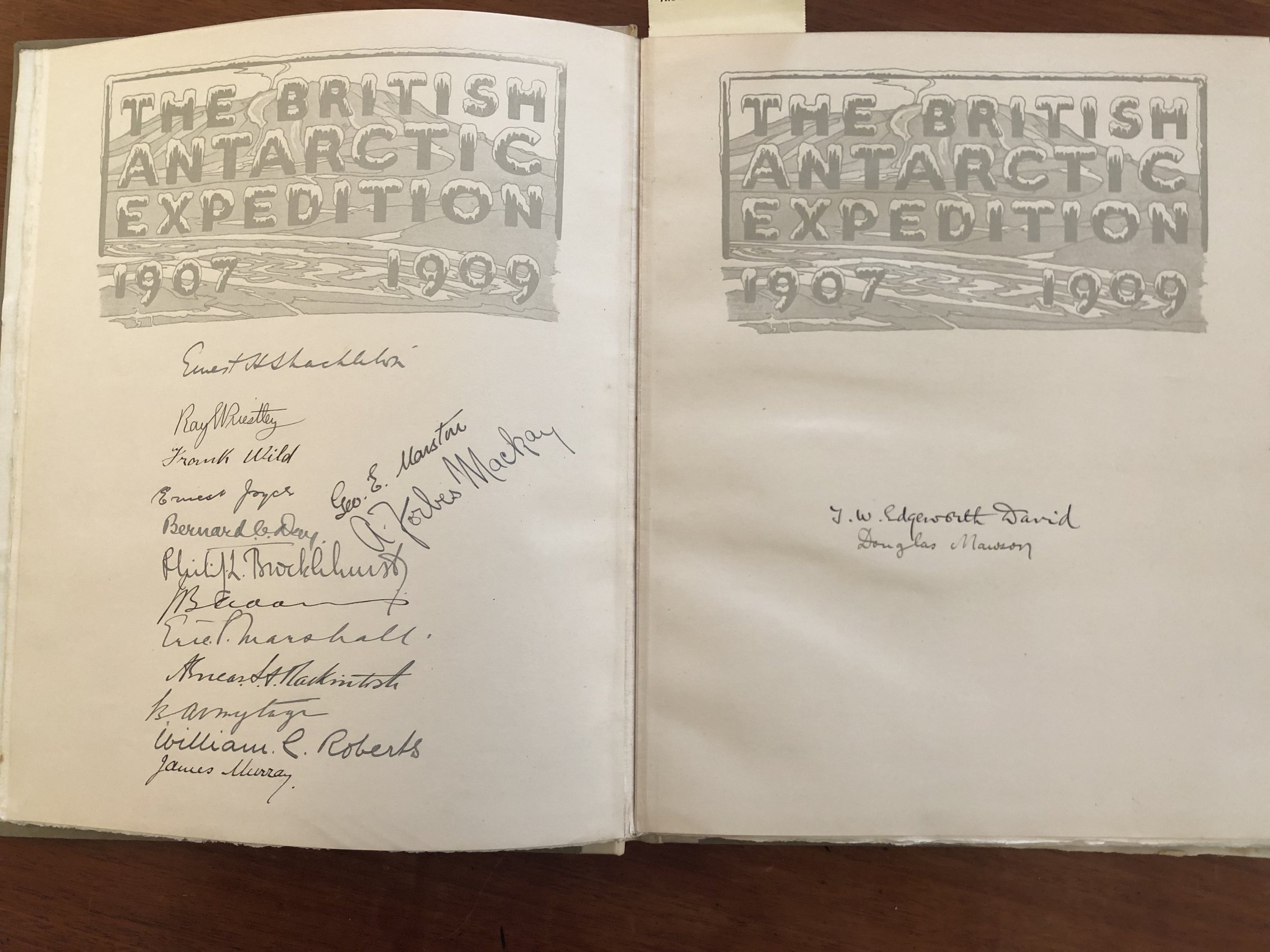

Reading this book brings me out of body. It is one of only 300 copies printed in London one hundred and nine years ago. The paper edges are rough as tree bark. It smells old. The photos and drawing inserts are hand glued in place. But what makes this copy particularly rare is that it's signed by Sir Ernest Shackleton with an inscription to his friend in Philadelphia, whom he thanks for his hospitality and shares "good wishes on the coming Christmas."

Page after worn page, I'm well aware that I am touching something that The Boss (not Springsteen) held a year before leaving for his famed Endurance expedition.

I marvel at descriptions of what the men endured, the list of supplies, the cost of the expedition--£44,380 (or £5,059,320.00/ $6,554,667.80 USD today).

When I look at the map I note how close the shore party was to the pole when Shackleton called it quits. Two degrees latitude. Two measly degrees. That’s New York to DC, Chicago to Indianapolis, Orlando to West Palm. It's also the difference between life and death.

The Athenaeum has both volumes of Heart of the Antarctic here, plus "The Antarctic Book," which contains poems (Erbus from Shackleton) and other interesting bits from the voyage. This version happens to be signed by the entire shore party, which included Frank Wild, who also joined Shackleton on the famed Endurance voyage.

After sitting with the books for hours, I leave them and step out into the muggy Philadelphia summer. I'm feeling adventurous. By Queen Village, I start hearing the lure of little voices. They tell me to go somewhere cool. Somewhere icy. Maybe Antarctica. Maybe the Arctic.

I end up at John's Water Ice on 7th Street. A medium cherry/lemon hits the spot.

Photos hand-glued in place.

They couldn't do better than Lipton's Tea???